Does art need a purpose?

I was having this discussion with a friend the other day, arguing in favor of art for art’s sake by making the analogy that art is like an elephant: what is the purpose of voi?

Like a great poem, concerto or watercolor, elephants serve no specific function, they simply exist, I contended. But considering the many ways in which they have been used by humans in Vietnam for centuries, I may have been harming my argument.

You’d hear them before you see them: a thundering of footfalls, shuddering crack of trampled undergrowth, piercing eruption of high-pitched echos. The Trung sisters’ army tore through Chinese occupiers, liberating the region with the help of terrific tusk strikes and the savage rampaging of 4,000-kilogram voi. Two hundred years later, Bà Triệu also took to the back of voi to bravely beat back brutal invaders from China.

These women, Vietnamese heroines that straddle the blurry line between ancient history and myth, are intrinsically linked to voi, which helps provide one of the most pervasive representations of the animals in Vietnam. They are loyal, fearsome comrades united with Vietnamese efforts for independence. In countless works of art, in movies and even in video games, the freedom-fighting women are depicted with voi the way a samurai is joined to a sword.

Elephants take part in transporting weapons and food for the battlefield.

Photo by Nhà xuất bản thông tấn via baodaklak.

Elephants are loyal, fearsome comrades united with Vietnamese efforts for independence

But elephants sometimes served as adversaries of the Vietnamese, as well. The Chiêm Thành (Champa) empire, which various Vietnamese forces fought against for several centuries, often employed them in their ranks. Notably, in the 11th century, General Trịnh Quốc Bảo, when faced with thousands of voi-mounted troops, created bamboo versions of the animals to practice on. And when the battle began, he attached fireworks to the plant facsimiles, and the discordant chaos of noise and color helped his army emerge victorious. The occasion is celebrated today during the recently established Trò Chiềng Festival in Thanh Hoa Province, during which the bamboo elephants are re-created for a martial arts game.

The great Nguyễn Huệ rode atop an elephant during some of his most decisive battles to drive out the Chinese, and the animals were prized by numerous rulers for their ability to transport men and materials; for the vantage point they offered generals as the highest seat on the battlefield; the psychological effect they had on opposing forces; and the utter strength they exhibited in the face of large forces. Seen as objects of prestige and signs of wealth, they were also often included in the spoils of war and as part of tributes offered between nation-states in the region.

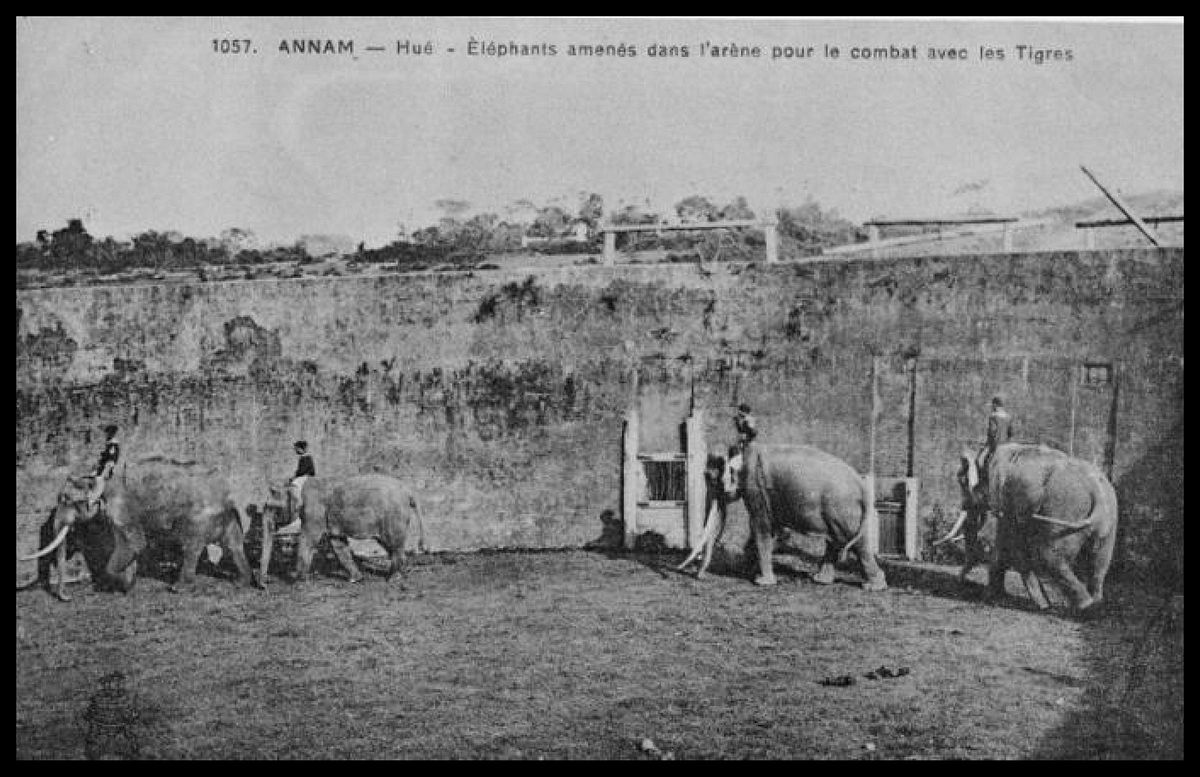

While voi were eventually used nominally during the wars against the French and Americans for the transfer of supplies, by the modern age, they had been replaced on the battlefield with more advanced weaponry. This, however, did not fully divorce voi from being seen as savage fighters. In one of the more flabbergasting footnotes of recent Vietnamese history, the Nguyen lords established the large Hổ Quyền Arena in Hue to stage battles to the death between voi and tigers. Because voi represented the dynasty’s courage and strength, the rulers all but ensured their victory by reportedly removing the tigers’ claws and teeth. The “sport” continued until the beginning of the 20th century, and people can still visit the arena in Hue today.

Voi were taken into the arena to fight tigers.

Photo by Pierre Dieulefils via wikipedia.

Hổ quyền Arena under Nguyen Dynasty. The arena had five tiger cages that opened into the battlefield.

Photos by Lưu Ly via Wikipedia.

Beyond bellicose purposes, Vietnamese have long used voi in forestry and agriculture. For proof, simply take a VND1,000 bill out of your wallet and look at the back: an elephant lugging lumber. Indeed, for centuries, residents of highland areas captured wild voi to transport rice, haul timber, construct homes and serve as ceremonial objects during festivals. Rather than struggle to complete the work by hand or pay exorbitant fees for domesticated buffalo, people understandably looked to them as a relatively free source of labor. In this, they became little different than a rake one fashions out of forest branches and stores in a shed.

Into the 21st century, when motorized means of clearing land and transporting goods fully replaced voi labor, the animals were not freed from the yolk of servitude. They became important sources of tourism revenue. Chained up and kept alive on meager rations, abused and deprived of social interactions, they were forced to perform in circus shows. And despite the great physical stress it causes, they were made to give rides to tourists who would post photos for social media cred.

Tourist voi rides in Dak Lak.

Photo by Michael Tatarski

Despite the great physical stress it causes, they were made to give rides to tourists who would post photos for social media cred

Efforts to end the rides in 2020 are a positive step, but it isn't certtain. While those formerly held for tourism purposes cannot be responsibly introduced back into wild habitats they aren’t adapted to, they are at least no longer being made to serve human interests. And in addition to those living relatively freely in sanctuaries and national forests, there are an estimated 60–100 elephants living in the wild in Vietnam, down from 2,000 in 1990. Freed from war, from labor, from tourism, they are finally able to exist independent of any purpose. Finally, voi can exist as art: beautiful blots of paint moving across nature’s parchment independent of human needs.